Analysing your interviews

The following video provides a really useful overview of how to conduct qualitative analysis, by manually coding transcripts. Personally, I prefer to code transcripts in NVivo, but these instructions are a great starting point to getting to grips with doing it by hand. I've transcribed the video and included the text below, so you have the option of either watching or reading.

[Thanks very much to the Southampton Education School for posting this!]

This is another of those difficult videos, where I can only give a brief overview of the numerous techniques associated with the analysis of your interviews. Unlike questionnaires, there are not standardised procedures to follow. Each research project involves different researchers, topics and contexts, and can be approached from a variety of perspectives.

For instance, I could do a content analysis. This is where I examine the interviews to identify the key words or paragraphs or themes. I could also do a discourse analysis, where I not only try to identify the main themes, I examine the way they are expressed and I examine the actual words used during the interview. I could do a relational analysis. This begins by identifying the concepts in my interview, similar to the content analysis, and then go beyond that to explore relationships between the concepts.

One thing all these approaches have in common is the use of direct quotations to support the conclusions. This is intended to bring the reader of the report into the reality of the situation that was studied. Despite this diversity, most approaches to analysing interviews involve three basic procedures: Firstly, noticing concepts and ideas relevant to your study. Secondly, we collect examples of these concepts and then thirdly, we analyse these concepts in order to find the commonalities, the differences, the patterns and the structures.

For the remainder of this video, I’m going to outline the strategies that I use to analyse interviews. There are plenty of good textbooks out there that focus just on interviewing and qualitative data. If you’re going to use interviews in your dissertation, I suggest you get one of the more specialist texts on the topic. However, I hope my strategies prove useful.

When I analyse my interviews, I adopt one of two strategies. I have an inductive approach - I use this with less structured interviews. And I have a combination deductive-inductive approach - I use this with structured and semi-structured interviews. I’ll talk you through the stages of the inductive approach first, because I use aspects of it in both approaches.

Inductive research firstly involves making specific observations, then identifying patterns with the observations, then making broader generalisations and eventually making tentative theories. Informally, we call this a bottom-up approach. An inductive approach in interviewing means letting the ideas and concepts and themes emerge from the data from the interview.

The first stage of my analysis is to identify the units of analysis. I do this by breaking up the interview into useful chunks of data. I could work with individual words, or groups of words or phrases, or I could use sentences and paragraphs. Sentences are usually a good starting point for beginners.

I start by putting each sentence of the interview onto a new line. If the sentence is rather long and involves several parts, I usually break this up into separate chunks of data. This is not just a formatting process, but this is a line-by-line analysis to get a feel for my data. I like working by hand, so I print out the interview. I double line space, and I put a large margin on the right-hand side to give me space to write.

Stage 2 is to go through my interview and give a one or two word summary or code to each chunk of line or data. The code should accurately describe the meaning of the segment of the text. This is called open coding. It is sometimes helpful to use a word from the sentence you are coding to help create the open code.

After open coding the entire interview, I make a list of all the codes, I look for similar codes, and I look for redundant codes. My objective is to reduce the long list of codes down to a smaller, more manageable number, maybe 20 to 25. This is an iterative process, so I often go back to my original data and check the new codes match. This is called constant comparison.

Stage 3 is to code my codes. Some people may call this ‘closed coding’. The aim is to identify five to seven overarching themes or categories that group your open codes. I usually do this in several stages. Firstly, reducing my 25 codes into 10 to 15 sub-codes, then narrowing those sub-codes down to my final five to seven overarching codes. Remember, there are no hard rules.

The final themes should reflect the purpose of the research. They should also be exhaustive. You must place all the data in a category, and they should be sensitising. They should be sensitive to what is in the data. For example, the themes and sub-themes should able to discriminate between leadership and transformational leadership.

At the end, there will be a range of themes. There will be:

Ordinary themes – the ones I expected.

Unexpected themes – the ones that surprise me and that I did not expect to find.

There will be hard to classify themes – the ones that contain ideas that do not necessarily fit into one theme, or that overlap with several other themes.

And major and sub-themes – that represent the major ideas or the minor secondary ideas. Sub-themes fit under the major themes in the write-up.

Stage 4 is to collect all the interview quotes within a theme and examine the ideas that make up the theme and sub-theme. I’m particularly interested in how they interact with each other. For instance, is there a sequence or order in which the information belongs? Similarly, I look for evidence of relationship between the overarching themes. I find that quotes that were initially hard to classify and fitted into several themes are a good starting point for finding relationships.

Stage 5. Remember, all this happens with the first interview transcript. I now repeat this process with the remainder of the transcripts. You may find new themes emerging as you go, so it is important to return to the earlier interviews and compare the new themes to the old ones and adjust your ideas. This is that constant comparison idea again.

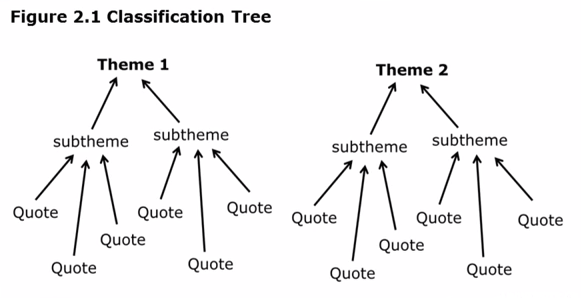

What you should slowly build up is something like a classification tree, moving from the specific to the general, starting with your interview data, moving to your codes, then to your sub-themes, and finally your themes.

The final stage is the write-up. When I’ve finished all the interviews, I construct a narrative from the themes, sub-themes and codes. This is a description of my themes, quotes from my interviews to support my ideas, and a discussion of the inter-relationships between the sub-themes and the themes.

This is, in essence, the theory I set out to develop. Sometimes I provide a visual display of the findings for my research report. This could be my classification tree.

My other approach to analysing interviews is to adopt a combination deductive-inductive approach. Remember, I use this approach with more structured interviews. Deductive research is commonly called ‘top-down’ research. We start with the theory, or a specific framework. We then test the theory by making observations, and eventually we confirm or reject the theory.

Okay, let’s apply this logic to my interviews. Stage 1 involves creating a set of themes or categories before I begin my analysis. This is a list of themes I derived from the literature, and is usually based around some theoretical concept. For example, if I was exploring leadership, my themes might be different aspects of leadership such as transactional, transformational, and distributed leadership. If I don’t have a pre-existing theory, I could select two or three of my interviews and use the inductive approach from before to create a framework for my analysis.

Stage 2 involves breaking up the interviews into chunks of data. For a more deductive approach, I tend to work with sentences and paragraphs.

Stage 3 involves allocating or labelling each sentence or paragraph with a closed code from my list of themes. I do this by having different coloured highlighting pens for each of my themes.

To do stage 4, I need to bring all the individual quotes for each theme together. For me, this literally involves cutting up my interviews with scissors, and putting all the quotes highlighted in a particular colour together. I then examine that theme and look for ideas within that theme. These become my sub-themes. Again, I’m interested in how each of the sub-themes and themes relate to each other.

When you have finished all the interviews, you construct a narrative from the themes and the codes. This is a description of my themes, quotes from my interviews to support my ideas I wish to present, and a discussion of the inter-relationships between these ideas.

One of the hard parts of qualitative analysis is finding a mechanical system to help you manage your interview data. Many people do it by hand, with transcripts printed onto paper, the marked up with pens and coloured markers, and using scissors to cut up the quotes so that they can grid them together. There are also a variety of computer programs, such as NVivo, MAXQDA, or ATLAS.ti designed especially for qualitative analysis. But be warned, they have long learning curves.

Finally, as you are working through your analysis stages, remember these basic principles:

Firstly, remember the key idea in both of these strategies is to allow new ideas and themes to emerge. This is one of the main reasons for doing interview type research.

Secondly, be systematic. Make sure you follow the same steps and procedures throughout your analysis.

Thirdly, be transparent. Make sure you tell the reader what you did and why you did it that way.

Finally, be coherent. Your interpretation should reflect patterns and ideas in the interviews.